Module

In abstract algebra, a module is a mathematical structure of which abelian groups and vector spaces are particular types. They have become ubiquitous in abstract algebra and other areas of mathematics that involve algebraic structures, such as algebraic topology, algebraic geometry, and algebraic number theory. A strong understanding of module theory is essential for anyone desiring to understand a wide array of graduate level mathematics and current mathematical research.

Contents |

[edit] Definition

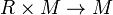

Let R be a ring (not necessarily with identity or commutative). A left R-module is an abelian group whose underlying set is endowed with an action by R respecting both the group structure of M and the ring structure of R. The R action is a map  . The image of

. The image of  under this map is typically written

under this map is typically written  , or just rm. The action is required to satisfy the following properties:

, or just rm. The action is required to satisfy the following properties:

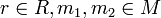

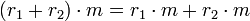

, for all

, for all

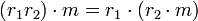

, and

, and

for all

for all

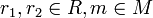

If the ring R has an identity, a module satisfying the additional axiom

-

for all

for all

is called unital or unitary.

A right R-module can be defined similarly.

[edit] Special types of modules

[edit] Vector Spaces

The archetype for modules, and the type one usually first encounters, is the vector space. Although vector spaces as encountered in applications or linear algebra courses usually use real or complex number scalars, the most general type of vector space is a module over a division ring. The fundamental commonality between all modules over a division ring is the existence of a basis for the module. Modules over more general rings do not necessarily have a basis, and those that do are called free modules.

[edit] Abelian Groups

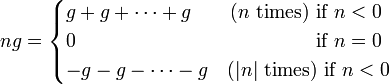

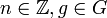

The Abelian groups are precisely the modules over  , the ring of integers. If G is an Abelian group (written additively), one defines the expression ng with

, the ring of integers. If G is an Abelian group (written additively), one defines the expression ng with  to mean

to mean

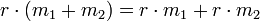

The commutative property for Abelian group operations and the rule for taking the inverse of a sum can be used to show that

- n(g1 + g2) = ng1 + ng2 for all

.

.

The rule for taking the inverse of a sum can also be used to show that

- (n1n2)g = n1(n2g) for all

,

,

checking cases separately for the different possibilities for the signs of n1,n2. Similarly, one can check several cases and show that

- (n1 + n2)g = n1g + n2g for all

The above three equations are the three axioms for the action of  on a

on a  -module.

-module.  -modules are therefore the same as Abelian groups.

-modules are therefore the same as Abelian groups.

If R is a ring with identity, then there is a ring homomorphism  . Through this map, we can canonically define the expression nm with

. Through this map, we can canonically define the expression nm with  and

and  . If M is a unital module, the expression nm has the same meaning in this sense as it does thinking of m as an Abelian group.

. If M is a unital module, the expression nm has the same meaning in this sense as it does thinking of m as an Abelian group.

This example already shows that not every module has a basis. That is, there is not always a subset of a module M such that every element of M can be expressed uniquely as a linear combination of elements of M. For instance, in the Abelian group  , increasing all of the coefficients of a linear combination by 2 will result in the same element of the group.

, increasing all of the coefficients of a linear combination by 2 will result in the same element of the group.

[edit] Modules over commutative rings

[edit] Free modules

[edit] Finitely generated modules

[edit] Other types of modules

A vast assortment of special types of modules have been studied --- more than can be discussed on this page. There are two approaches to abstractly defining special types of modules. First, one may allow the ring R to be arbitrary and study all modules with a certain structural property definable without using properties specific to R. Examples of this type include:

- free modules, locally free modules, and stably free modules

- finitely-generated modules

- projective and injective modules.

- Noetherian and Artinian modules.

- semi-simple and simple modules.

Second, one may consider arbitrary modules over a special class of rings. Examples of this type include:

- vector spaces and abelian groups

- modules over a principal ideal domain

- Galois modules

Of course, one may mix these two approaches, studying modules with certain structural properties over a special type of ring. Also, practitioners in most fields of higher mathematics study all modules manifest through a natural process within that field, such as homology with coefficients of topological spaces or class groups of number fields as Galois modules. For a more complete list of special types of modules, see the related articles subpage.

[edit] The category of R-modules

The morphisms in the category of R-modules are defined respecting the abelian group structure and the action of R. That is, a morphism  is a homomorphism

is a homomorphism  of the abelian groups M and M' such that

of the abelian groups M and M' such that  for all

for all  .

.

The category of modules over a fixed commutative ring R are the prototypical abelian category; this statement is deeper than it may appear, in fact every small abelian category is equivalent to a full subcategory of some category of modules over a ring. This result is due to Freyd and Mitchell.

[edit] Examples

- The category of

-modules is equivalent to the category of abelian groups.

-modules is equivalent to the category of abelian groups.

| |

Some content on this page may previously have appeared on Citizendium. |