Rotation matrix

In mathematics and physics a rotation matrix is synonymous with a 3×3 orthogonal matrix, which is a real 3×3 matrix R satisfying

where T stands for the transposed matrix and R−1 is the inverse of R.

Contents |

Connection of an orthogonal matrix to a rotation

In general a motion of a rigid body (which is equivalent to an angle and distance preserving transformation of affine space) can be described as a translation of the body followed by a rotation. By a translation all points of the body are displaced, while under a rotation at least one point of the body stays in place. Let the the fixed point be O. By Euler's theorem follows that then not only the point is fixed but also an axis—the rotation axis— through the fixed point. Write  for the unit vector along the rotation axis and φ for the angle over which the body is rotated, then the rotation operator on ℝ3 is written as ℛ(φ, n̂).

for the unit vector along the rotation axis and φ for the angle over which the body is rotated, then the rotation operator on ℝ3 is written as ℛ(φ, n̂).

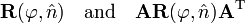

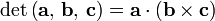

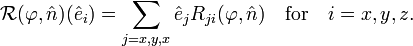

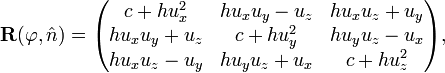

Erect three Cartesian coordinate axes with the origin in the fixed point O and take unit vectors  along the axes, then the 3×3 rotation matrix

along the axes, then the 3×3 rotation matrix  is defined by its elements

is defined by its elements

:

:

In a more condensed notation this equation can be written as

Given a basis of the linear space ℝ3, the association between a linear map and its matrix is one-to-one.

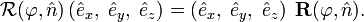

A rotation  (for convenience sake the rotation axis and angle are suppressed in the notation) leaves the shape of a rotated rigid body intact, so that all distances within the body are invariant. If the body is 3-dimensional—it contains three linearly independent vectors with origins in the invariant point—it holds that for any pair of vectors

(for convenience sake the rotation axis and angle are suppressed in the notation) leaves the shape of a rotated rigid body intact, so that all distances within the body are invariant. If the body is 3-dimensional—it contains three linearly independent vectors with origins in the invariant point—it holds that for any pair of vectors  and

and  in ℝ3 the inner product is invariant, that is,

in ℝ3 the inner product is invariant, that is,

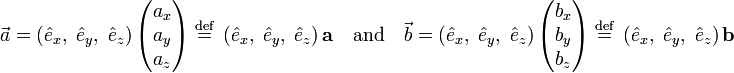

A linear map with this property is called orthogonal. It is easily shown that a similar vector-matrix relation holds. First we define column vectors (stacked triplets of real numbers given in bold face):

and observe that the inner product becomes by virtue of the orthonormality of the basis vectors

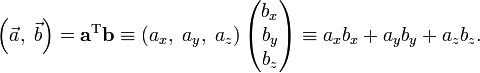

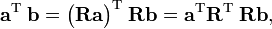

The invariance of the inner product under the rotation operator  leads to

leads to

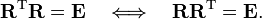

since this holds for any pair a and b it follows that a rotation matrix satisfies

where E is the 3×3 identity matrix. For finite-dimensional matrices one shows easily

A matrix with this property is called orthogonal. So, a rotation gives rise to a unique orthogonal matrix.

Conversely, consider an arbitrary point P in the body and let the vector  connect the fixed point O with P. Expressing this vector with respect to a Cartesian frame in O gives the column vector p (three stacked real numbers). Multiply p by the orthogonal matrix R, then p′ = Rp represents the rotated point P′ (or, more precisely, the vector

connect the fixed point O with P. Expressing this vector with respect to a Cartesian frame in O gives the column vector p (three stacked real numbers). Multiply p by the orthogonal matrix R, then p′ = Rp represents the rotated point P′ (or, more precisely, the vector  is represented by column vector p′ with respect to the same Cartesian frame). If we map all points P of the body by the same matrix R in this manner, we have rotated the body. Thus, an orthogonal matrix leads to a unique rotation.

is represented by column vector p′ with respect to the same Cartesian frame). If we map all points P of the body by the same matrix R in this manner, we have rotated the body. Thus, an orthogonal matrix leads to a unique rotation.

Note that the Cartesian frame is fixed here and that points of the body are rotated, this is known as an active rotation. Instead, the rigid body could have been left invariant and the Cartesian frame could have been rotated, this also leads to new column vectors of the form p′ ≡ Rp, such rotations are referred to as passive.

Properties of an orthogonal matrix

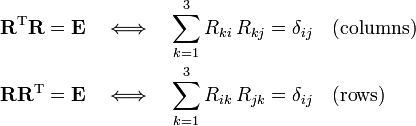

Writing out matrix products it follows that both the rows and the columns of the matrix are orthonormal (normalized and orthogonal). Indeed,

where δij is the Kronecker delta.

Orthogonal matrices come in two flavors: proper (det = 1) and improper (det = −1) rotations. Indeed, invoking some properties of determinants, one can prove

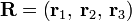

Compact notation

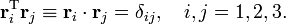

A compact way of presenting the same results is the following. Designate the columns of R by r1, r2, r3, i.e.,

.

.

The matrix R is orthogonal if

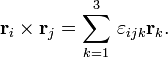

The matrix R is a proper rotation matrix, if it is orthogonal and if r1, r2, r3 form a right-handed set, i.e.,

Here the symbol × indicates a

cross product and  is the

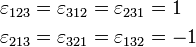

antisymmetric Levi-Civita symbol,

is the

antisymmetric Levi-Civita symbol,

and  if two or more indices are equal.

if two or more indices are equal.

The matrix R is an improper rotation matrix if its column vectors form a left-handed set, i.e.,

The last two equations can be condensed into one equation

by virtue of the the fact that the determinant of a proper rotation matrix is 1 and of an improper rotation −1. This was proved above, an alternative proof is the following: The determinant of a 3×3 matrix with column vectors a, b, and c can be written as scalar triple product

.

.

It was just shown that for a proper rotation the columns of R are orthonormal and satisfy,

Likewise the determinant is −1 for an improper rotation.

Explicit expression of rotation operator

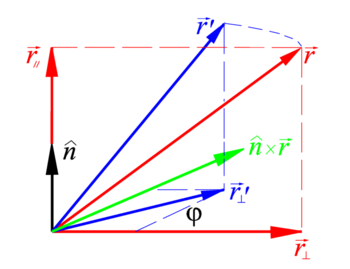

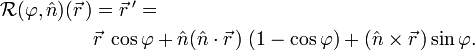

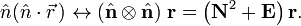

Let  be a vector pointing from the fixed point O of a rigid body to an arbitrary point P of the body. A rotation of this arbitrary vector around the unit vector n̂ over an angle φ can be written as

be a vector pointing from the fixed point O of a rigid body to an arbitrary point P of the body. A rotation of this arbitrary vector around the unit vector n̂ over an angle φ can be written as

where • indicates an inner product and the symbol × a cross product.

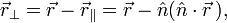

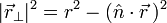

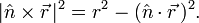

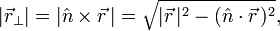

It is easy to derive this result. Indeed, decompose the vector to be rotated into two components, one along the rotation axis and one perpendicular to it (see the figure on the right)

and

so that, in view of |n̂| = 1,

and from |a×b|2 = a2b2 − (a⋅b)2 follows

Upon rotation, the component of the rotated vector along the rotation axis is invariant, only its component orthogonal to the rotation axis changes. By virtue of the following fact (in words: length of basis vector along x-axis is length of basis vector along y-axis):

the rotation property simply is

Hence

Some reshuffling of the terms gives the required result.

Explicit expression of rotation matrix

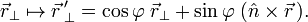

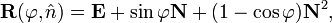

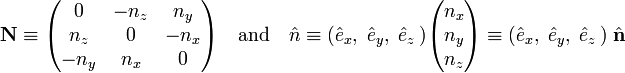

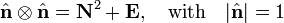

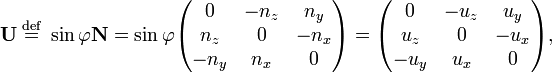

It will be shown that

where (see cross product for more details)

Note further that the dyadic product satisfies (as can be shown by squaring N),

and that

Translating the result of the previous section to coordinate vectors and substituting these results gives

which gives the desired result for the rotation matrix. This equation is identical to Eq. (2.6) of Biedenharn and Louck[1], who give credit to Leonhard Euler (ca. 1770) for this result.

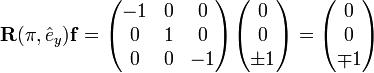

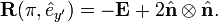

For the special case φ = π (rotation over 180°), equation (1) can be simplified to

so that

which sometimes[2] is referred to as reflection over a line, although it is not a reflection.

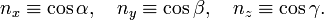

Equation (1) is a special case of the transformation properties given on p. 7 of the classical work (first edition 1904) of Whittaker[3]. To see the correspondence with Whittaker's formula, which includes also a translation over a displacement d and who rotates the vector (x−a, y−b, z−c), we must put equal to zero: a, b, c, and d in Whittaker's equation. Furthermore Whittaker uses that the components of the unit vector n are the direction cosines of the rotation axis:

Under these conditions the rotation becomes

Vector rotation

Sometimes it is necessary to rotate a rigid body so that a given vector in the body (for instance an oriented chemical bond in a molecule) is lined-up with an external vector (for instance a vector along a coordinate axis).

Let the vector in the body be f (the "from" vector) and the vector to which f must be rotated be t (the "to" vector). Let both vectors be unit vectors (have length 1). From the definition of the inner product and the cross product follows that

where φ is the angle (< 180°) between the two vectors. Since the cross product f × t is a vector perpendicular to the plane of both vectors, it is easily seen that a rotation around the cross product vector over an angle φ moves f to t.

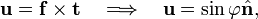

Write

where  is a unit vector.

Define accordingly

is a unit vector.

Define accordingly

so that

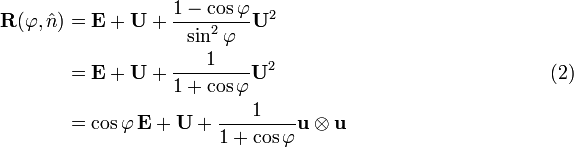

The last equation, which follows from U2 = u⊗u − sin2φ E, is Eq. (3) of Ref. [4] after substitution of

Indeed, write the rotation matrix in full, using the short-hand notations c = cos φ and h = (1-c)/(1-c2)

which is the matrix in Eq. (3) of Ref. [4].

If the vectors are parallel, f = t, then u = 0, U = 0 and f•t = cosφ = 1,

so that the equation is well-defined—it gives R(φ, n) = E, as expected.

Provided f and t are not anti-parallel, the matrix  can be computed easily and quickly. It requires not much more than the computation of the inner and cross product of f and t.

can be computed easily and quickly. It requires not much more than the computation of the inner and cross product of f and t.

Case that "from" and "to" vectors are anti-parallel

If the vectors f and t are nearly anti-parallel, f ≈ − t, then f•t = cosφ ≈ − 1, and the denominator in Eq. (2) becomes zero, so that Eq. (2) is not applicable. The vector defining the rotation axis is nearly zero: u ≡ f × t ≈ f × (−f) ≈ 0.

Clearly, a two-fold rotation (angle 180°) around any rotation axis perpendicular to f will map f onto −f. This freedom in choice of the two-fold axis is consistent with the indeterminacy in the equation that occurs for cosφ = −1.

Since −E (inversion) sends f to −f, one could naively assume that all position vectors of the rigid body may be inverted by −E. However, if the rigid body is not symmetric under inversion (does not have a symmetry center), inversion turns the body into a non-equivalent one. For instance, if the body is a right-hand glove, inversion sends it into a left-hand glove; it is well-known that a right-hand and a left-hand glove are different.

Recall that f is a unit vector. If f is on the z-axis, |fz| = 1, then the following rotation around the y-axis turns f into −f:

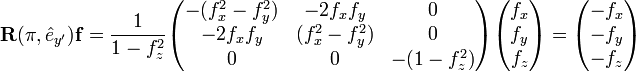

If f is not on the z-axis, fz ≠ 1, then the following orthogonal matrix sends f to −f and hence gives a 180° rotation of the rigid body

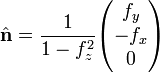

To show this we insert

into the expression for rotation over 180° introduced earlier:

Note that the vector  is normalized, because f is normalized, and that it lies in the x-y plane normal to the plane spanned by the z-axis and f; it is in fact a unit vector along a rotated y-axis obtained by rotation around the z-axis.

is normalized, because f is normalized, and that it lies in the x-y plane normal to the plane spanned by the z-axis and f; it is in fact a unit vector along a rotated y-axis obtained by rotation around the z-axis.

Given f = (fx, fy, fz), the matrix  is easily and quickly calculated. The matrix rotates the body over 180° sending f to −f exactly. When −f and t are close, but not exactly equal, the earlier rotation formula Eq. (2), may be used to perform the final (small) rotation of the body that lets −f and t coincide exactly.

is easily and quickly calculated. The matrix rotates the body over 180° sending f to −f exactly. When −f and t are close, but not exactly equal, the earlier rotation formula Eq. (2), may be used to perform the final (small) rotation of the body that lets −f and t coincide exactly.

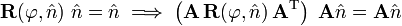

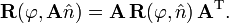

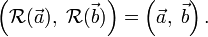

Change of rotation axis

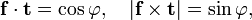

Euler's theorem states that a rotation is characterized by a unique axis (an eigenvector with unit eigenvalue) and a unique angle. As a corollary of the theorem follows that the trace of a rotation matrix is equal to

and hence the trace depends only on the rotation angle and is independent of the axis. Let A be an orthogonal 3×3 matrix (not equal to E), then, because cyclic permutation of matrices under the trace is allowed (i.e., leaves the trace invariant),

As a consequence it follows that the two matrices

describe a rotation over the same angle φ but around different axes. The eigenvalue equation can be transformed

which shows that the transformed eigenvector is the rotation axis of the transformed matrix, or

References

- ↑ L. C. Biedenharn and J. D. Louck, Angular Momentum in Quantum Physics, Addison-Wesley, Reading, Mass. (1981) ISBN 0-201-13507-8

- ↑ Wikipedia Retrieved July 20, 2009

- ↑ E. T. Whittaker, A Treatise on the Dynamics of Particles and Rigid Bodies, Cambridge University Press (1965)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 T. Möller and J. F. Hughes, J. Graphics Tools, 4 pp. 1–4 (1999).

around n̂ over φ.

around n̂ over φ.

![\vec{r}\,' = \hat{n} (\hat{n}\cdot\vec{r}\,) + \left[\vec{r}- (\hat{n}\cdot\vec{r}\,) \hat{n}\right]\cos\varphi+(\hat{n}\times\vec{r}\,)\sin\varphi.](images/math/3/6/1/361d646e81e702b83e4668afea9bfd62.png)

![\begin{align}

\mathbf{r}' &= \left[\cos\varphi\; \mathbf{E} +(1-\cos\varphi)(\mathbf{N}^2 + \mathbf{E}) + \sin\varphi \mathbf{N} \right] \mathbf{r} \\

&= \left[\mathbf{E} + (1-\cos\varphi) \mathbf{N}^2 + \sin\varphi \mathbf{N}\right] \mathbf{r},

\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad(1)

\end{align}](images/math/f/e/6/fe6af86a214f8523d028a0efe81d0572.png)

![\begin{align}

x' &= x-(1-\cos\varphi)\left[x\;\sin^2\alpha - y\;\cos\alpha\cos\beta - z\;\cos\alpha\cos\gamma\right]

+\left[z\;\cos\beta- y\;\cos\gamma\right]\sin\varphi \\

y' &= y-(1-\cos\varphi)\left[y\;\sin^2\beta - z\;\cos\beta\cos\gamma - x\;\cos\beta\cos\alpha\right]

+\left[x\;\cos\gamma- z\;\cos\alpha\right]\sin\varphi \\

z' &= z-(1-\cos\varphi)\left[z\;\sin^2\gamma - x\;\cos\gamma\cos\alpha - y\;\cos\gamma\cos\beta\right]

+\left[y\;\cos\alpha- x\;\cos\beta\right]\sin\varphi \\

\end{align}](images/math/a/0/7/a07211a1a7e03a479336ada0ecac12a4.png)

![\mathrm{Tr}[\mathbf{R}(\varphi, \hat{n})] = 2\cos\varphi +1,](images/math/7/e/4/7e4337aac187ba63bc70c3072a982654.png)

![\mathrm{Tr}[\mathbf{A} \mathbf{R}(\varphi, \hat{n}) \mathbf{A}^\mathrm{T}] =

\mathrm{Tr}[ \mathbf{R}(\varphi, \hat{n}) \mathbf{A}^\mathrm{T}\mathbf{A}] = \mathrm{Tr}[\mathbf{R}(\varphi, \hat{n})] .](images/math/e/f/8/ef81c924bde7ba17bac999010c47358b.png)