Hermitian operator

An Hermitian operator is the physicist's version of an object that mathematicians call a self-adjoint operator. It is a linear operator on a vector space V that is equipped with positive definite inner product. In physics an inner product is usually notated as a bra and ket, following Dirac. Thus, the inner product of Φ and Ψ is written as,

Here "Φ is in the bra" and "Ψ is in the ket".

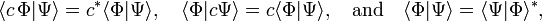

Physicists use the convention

where  is the complex conjugate of

is the complex conjugate of  .

.

Physicists name the pair of linear operators  each other's Hermitian adjoint when they are connected through the turn-over rule,

each other's Hermitian adjoint when they are connected through the turn-over rule,

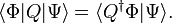

This is expressed by the statement: "the operator Q-dagger is the Hermitian adjoint of Q". Note that the second upright bar surrounding an operator in a bra-ket does not serve any function, some physicists omit it. Evidently, since the turn-over rule may bring the operator from ket to bra and back from bra to ket,

The linear operator Q is called Hermitian if it is equal to its Hermitian adjoint. That is, if

then Q is Hermitian.

Except for problems associated with scattering of (nearly) free particles, it is common in physics not to consider the domain or range of the adjoint pair. The range and domain are usually taken to be the whole vector space V. Doing this, physicists assume implicitly that the vector space V is of finite dimension.

Properties

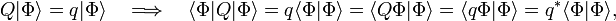

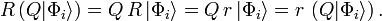

Hermitian operators have real eigenvalues. Indeed, let

from which follows  , that is, the eigenvalue q is real.

, that is, the eigenvalue q is real.

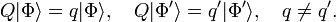

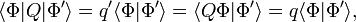

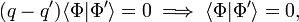

Eigenvectors of a Hermitian operator associated with different eigenvalues are orthogonal. Indeed, let

Then

or, since q - q′ ≠ 0,

which is expressed by stating that Φ and Φ′ are orthogonal (have zero inner product). In case of finite degeneracy (finite number of linearly independent eigenvectors associated with the same eigenvalue) orthogonality is not assured. However, it is always possible to orthogonalize a finite set of linearly independent set of vectors, i.e., to form linear superpositions such that the new set is orthogonal.

It can be shown that a Hermitian operator on a finite dimensional vector space has as many linearly independent eigenvectors as the dimension of the space. This means that its eigenvectors can serve as a basis of the space. Physicists often assume this to be true for operators on infinite dimensional spaces, but here one should be careful. For instance, the normalizable eigenstates of a hydrogen-like Hamilton operator do not span the whole vector space that they belong to; they do not form a basis of the Hilbert space that they belong to.

Commuting Hermitian operators

Two operators, Q and R, are said to commute, if their commutator [Q, R] is the zero operator, i.e., if

The zero operator maps any vector of the space onto the zero vector.

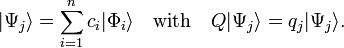

Commuting operators can have common eigenvectors. If Q and R commute, a set of vectors can be found that are simultaneously eigenvectors of both Hermitian operators. Conversely, if a set of common eigenvectors exist that spans the whole space, then Q and R commute.

To prove these statements, we let R have n orthogonal eigenvectors  with an eigenvalue r that is n-fold degenerate, i = 1, ..., n. These eigenvectors span a linear space called the eigenspace of R belonging to r. (Note that the special case of no degeneracy follows by taking n = 1). Now,

with an eigenvalue r that is n-fold degenerate, i = 1, ..., n. These eigenvectors span a linear space called the eigenspace of R belonging to r. (Note that the special case of no degeneracy follows by taking n = 1). Now,

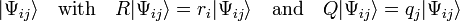

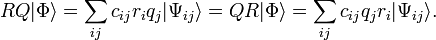

If  is an eigenvector of R with eigenvalue r, and R commutes with Q, then

is an eigenvector of R with eigenvalue r, and R commutes with Q, then  is also an eigenvector of R with eigenvalue r. This follows by considering the expressions between brackets on the left- and rightmost side of this equation. In other words,

is also an eigenvector of R with eigenvalue r. This follows by considering the expressions between brackets on the left- and rightmost side of this equation. In other words,  belongs to the eigenspace associated with r, i.e., the eigenspace is stable (invariant) under Q. If

belongs to the eigenspace associated with r, i.e., the eigenspace is stable (invariant) under Q. If  belongs to an eigenspace of R, then

belongs to an eigenspace of R, then  belongs to the same eigenspace.

belongs to the same eigenspace.

We are now faced with the problem of finding the eigenvectors of Q on a finite-dimensional eigenspace of R. This problem is solvable (for instance by turning it into the corresponding matrix problem) and we obtain eigenvectors  of Q,

of Q,

Since the  in this expression are all eigenvectors of R with eigenvalue r, it follows that

in this expression are all eigenvectors of R with eigenvalue r, it follows that

Hence, from the commutation follows the first statement: there exists a set  of common eigenvectors. If the eigenvectors of R (with different eigenvalues) span the total vector space, then this set spans the whole space, too.

of common eigenvectors. If the eigenvectors of R (with different eigenvalues) span the total vector space, then this set spans the whole space, too.

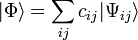

Conversely, assume that the set of common eigenvectors

span the whole vector space.

Then for an arbitrary vector  it holds that

it holds that

so that

Since for any element of the vector space it holds that RQ = QR, the linear operators commute.

Example

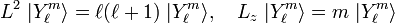

The total orbital angular momentum operator squared commutes with its z-component

It can be shown that spherical harmonics are eigenvectors of both commuting operators simultaneously

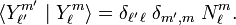

Hence

Here  is a normalization constant (for spherical harmonics usually equal unity) and the δ's are Kronecker deltas (zero if the subscripts are different, one otherwise).

is a normalization constant (for spherical harmonics usually equal unity) and the δ's are Kronecker deltas (zero if the subscripts are different, one otherwise).

![\big[ Q, R \big] \equiv QR-RQ = 0.](images/math/f/5/f/f5f6bc0cf6c7bddbed3f43de39f50021.png)

![[L^2, L_z] = 0. \;](images/math/b/5/5/b55aa09639237410aea1398a5c6728b5.png)